What Is a Christian Martyr?

What is a Christian martyr and why does our defintion matter?

After the recent murder of a public figure known both for his political activism and his profession of faith in Jesus, there is renewed interest in Christian martyrdom: What is a Christian martyr? The church has always used this word carefully, and it’s worth revisiting what Scripture and early Christian history have to say.

From Courtroom to Cross

The English word martyr comes from the Greek word martys, which at first had nothing to do with death or religion. It simply meant “witness.” In a legal context, a martys testified to what he had seen or heard.

John describes his gospel (a biography of the life of Jesus) as his martyria (testimony) (John 1:19). It contains what he saw and heard in his time with Jesus. Later, a person who told others what he had seen and heard about the death and resurrection of Jesus was called a martys as well. For example, the apostles who “bear witness” to the resurrection (Acts 2:32; 3:15; 5:32).

Martyrs and Death

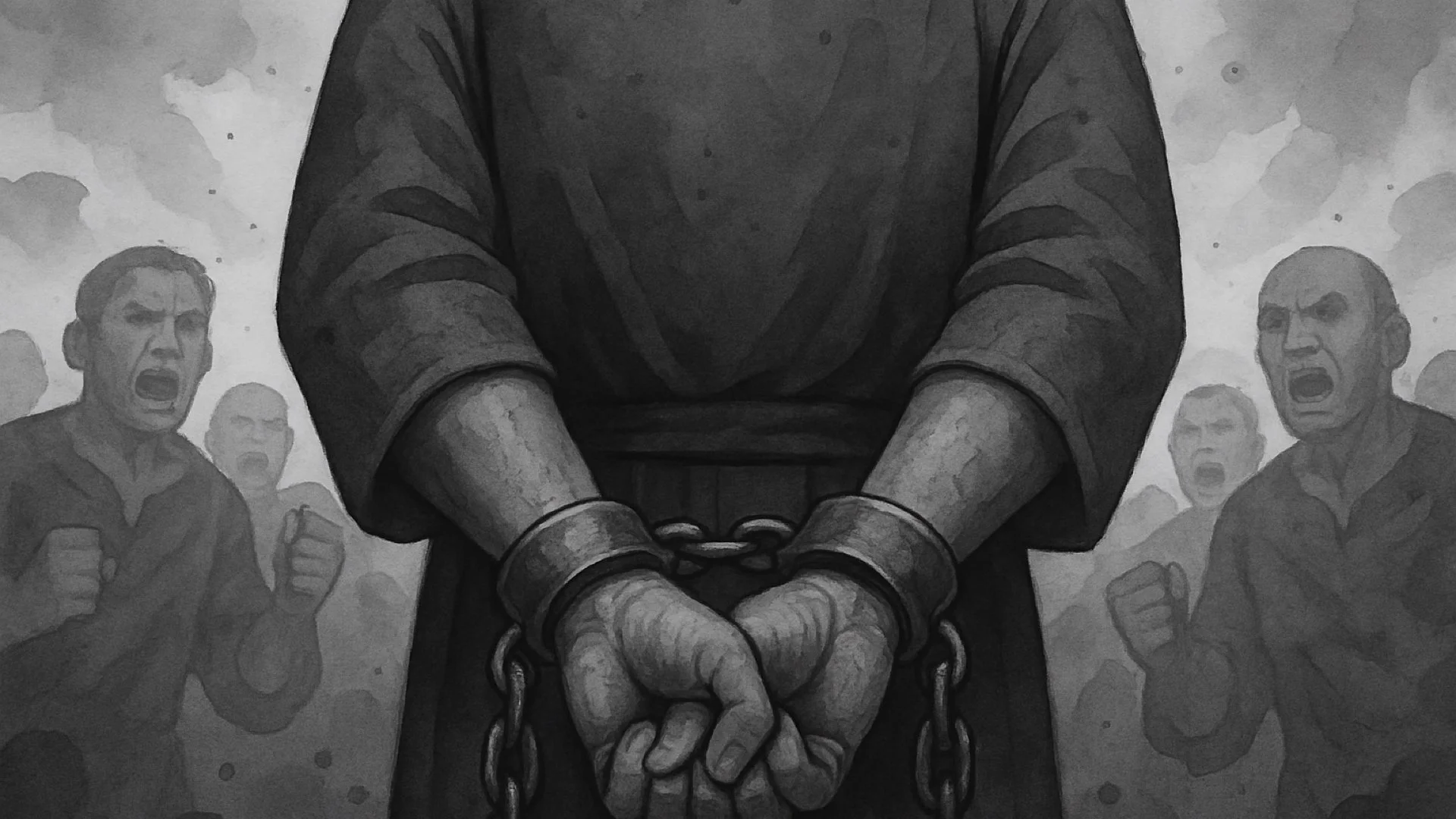

Stephen, in Acts 7, is the first to be remembered as a martyr because he was killed for his witness about Jesus. He testified that Jesus was Lord, and for this he was stoned. James, one of the apostles, was executed for the same reason (Acts 12:2). They weren’t murdered for any wrongdoing, but only because of their testimony about Jesus and their resemblance to him. For proclaiming who Jesus was and embodying his way of life, they shared in his sufferings.

Peter helps us draw an important boundary: “If you suffer, it should not be as a murderer or thief or any other kind of criminal, or even as a meddler. However, if you suffer as a Christian, do not be ashamed, but praise God that you bear that name” (1 Peter 4:15–16).

That word “meddler” is the English translation of a rare Greek term meaning a busybody: someone who interferes in matters that don’t belong to them. Peter’s point is clear: suffering for meddling, crime, or quarrelsomeness is not the same as suffering for Christ. Instead, Christians are called to be “blameless and pure, children of God without fault in a warped and crooked generation” (Philippians 2:15). Our lives should give no reason for reproach except our witness about Jesus and our resemblance to him.

Paul echoes this in his letter to the Corinthians: “To this very hour we go hungry and thirsty, we are in rags, we are brutally treated, we are homeless. We work hard with our own hands. When we are cursed, we bless; when we are persecuted, we endure it; when we are slandered, we answer kindly. We have become the scum of the earth, the garbage of the world—right up to this moment” (1 Corinthians 4:12–13).

According to tradition, Paul and most of the apostles were eventually killed for their testimony about Jesus. And from Paul’s own words, it’s clear that they were martyred while working hard, blessing their enemies, enduring persecution, and responding to lies with kindness. They were killed only because they bore witness about Jesus and because their lives resembled his.

Martyrdom and the Early Church

In the first three centuries of Christianity, many were martyred by Roman authorities. They were offered freedom if they would merely burn incense to Caesar or deny Christ. Those who refused were killed. The church honored them as martyrs, witnesses who confessed Jesus as Lord even to death.

One of the earliest and most inspiring examples was Polycarp, the elderly bishop of Smyrna. When soldiers came to arrest him, he watered their horses and welcomed them into his home with a meal. Later, in the arena, he calmly refused to renounce his faith in Jesus. Polycarp bore witness in both his words about Jesus and his resemblance to Jesus.

Early Christian leaders were careful not to confuse martyrdom with other kinds of death. Tertullian, a pastor writing around AD 200, said, “Those who persecute us are compelled to confess that in our case alone men are put to death for the name—not for any crime.” Origen, another early theologian, added, “It is not the punishment but the cause that makes the martyr.”

To be a martyr was not to die tragically, or even to die while defending values connected to Christianity. It was to die for one reason: a refusal to renounce allegiance to Christ while behaving like Christ.

Why This Matters

We honor the Christian martyrs of history best when we apply the word “martyr” only to those who were killed because of their testimony about Jesus and their resemblance to him.

Such clarity protects us today. It keeps us from conflating partisan political activism with faithful gospel proclamation. And it reminds us that while every murder is evil and tragic, not every Christian who is killed is killed because of their Christian witness.

Martyrs, however, die for one reason alone: their loyalty and likeness to Christ. And for that reason their deaths become the greatest witness of all. Their blood amplifies their testimony about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus—and not any other institution, ideology, or cause.

This is why Tertullian could say, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.” Their lives and their deaths proclaimed Christ so powerfully that many who watched recognized the evil of their murder, the innocence of their lives, the truth of their message, and came to believe in Jesus. By the Spirit, the church grew through these faithful witnesses who loved Christ more than life itself.