What exactly was America’s war ethic during World War II?

What exactly was America’s war ethic during World War II?

Depends.

There’s the official policy stated at the beginning of the war: American military leaders announced they would be differentiating noncombatants from combatants. The air force declared it would bomb only facilities which directly supported the enemy’s military.

“During World War II the United States Air Forces (AAF) enunciated a policy of avoiding indiscriminate attacks against German civilians. …American airmen were to make selective strikes against precise military and industrial targets, avoiding direct attacks on the populace” (1).

This official policy ensured the public that any killing of civilians would be accidental, an unintended unpreventable consequence of attacks on valid military or industrial targets directly related to the enemy’s war effort.

“This stated policy seemed to set the United States morally apart from the other warring nations. Germany, Japan and Great Britain imposed no such limitation on themselves and were quite willing openly to attack civilian populations.”(2)

Ronald Shaffer – a military historian – argues that while U.S. military leaders generally opposed bombing civilians they did so out of practical and not moral concerns and their opposition did not last. With planes and ammunition in limited supply, Shaffer claims U.S. military leaders did not want to waste their resources destroying non-military targets they saw as less effective at defeating the enemy. But by the end of the war America was spending a great number of resources on the destruction of civilian populations.(1)

“Locked in a struggle with a potent and feared enemy, they discovered that their bombers could not operate as effectively as they had imagined before the war. …It is possible that they eventually felt constrained to act against their true principles, that a cruel reality had forced them to compromise their convictions.”(2)

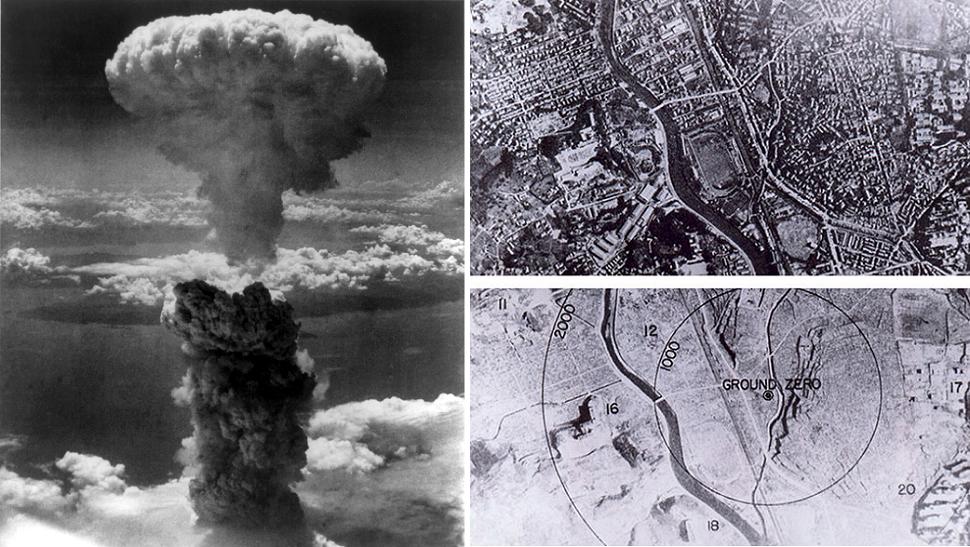

So, U.S. leaders announced their adherence to noncombatant immunity at the start of the war but bombed the civilian population of Dresden in February 1945, Tokyo in March 1945, and killed 150,000-246,000 men, women and children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of 1945.

“…the raids on Japan marked the ultimate demise of the prewar theory of precision bombardment. Once again the grim logic of war had prevailed over those who sought to find some surgically precise method for the application of force. In these assaults near the end of the war there was not even the pretense of restraint.”(3)

One historian defends this lack of restraint by reminding us that Americans were tired of being at war and demanded a quick end to it. America’s leadership, he says, had pressed military leaders to win nothing less than an unconditional surrender…and to do so quickly.

“…had any Allied commander been found guilty of bringing less than the total possible force to bear on the enemy, thereby to shorten the war and ‘bring the boys home,’ he would have been well advised not to appear unprotected on Main Street, U.S.A. In these circumstances it is not surprising that questions about the morality of their methods did not take first place in the minds of military commanders.”(3)

Sources:

- 1. Ronald Schaffer, “American Military Ethics in World War II: The Bombing of German Civilians,” Journal of American History 67 (September 1980)

- 2. Louis A. Manzo, Morailty in War Fighting and Strategic Bombing in World War II (Air Force Historical Foundation, 1992)

- 3. MacIsaac, Strategic Bombing in World War II

Shaun Groves

Shaun Groves

Jenn says:

I don’t think the bombing of Dresden was ever mentioned in our school history books. They talked about Hiroshima and Nagasaki because they had to, but it was always spun in a more flattering light. I remember very clearly the first time I read about Dresden; it was like when Toto opened the curtain on the Great and Powerful Oz.

Sheila Warner says:

I just found this series. Left out in this part on the Just War doctrine is the tactics of the Japanese during WW II. Kamakazi bombers, and fight to the death soldiers, exposed Americans to the most barbaric battle tactics they had ever witnessed. It became clear that, to minimize the huge numbers of Allies being killed in the Pacific, extreme measures needed to be taken. The West is not alone in pursuing total war.